The situation is this: Republicans face the very real possibility of losing both the White House and their Senate majority in November. Ginsburg's death creates what many conservatives view as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to move the makeup of the court from its current lineup of five conservative justices to four liberal justices to a more dominant 6-3 majority. And for Trump to appoint a third young justice -- both Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh are under 60 -- who could help serve as the conservative foundation of the court for decades to come.

The countervailing force against all of that is tradition, the weight of history and just how much a senator's past statements actually matter.

See, back in the spring of 2016, then-President Barack Obama moved to fill the seat left vacant by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. Obama chose Merrick Garland, a moderate that Obama quite clearly hoped would be a sort of consensus pick that senators in both parties would vote to confirm. It didn't work out that way. McConnell -- then, as now, the leader of the Senate -- insisted that not only would Garland not receive a full Senate floor vote but also that he would not even get a confirmation hearing in front of the Judiciary Committee.

Why? Because, according to McConnell, Obama was on his way out of office -- term-limited at the end of 2016 -- and that ruled out the Senate considering the pick.

"Of course the American people should have a say in the court's direction," McConnell said at the time. "It is a president's constitutional right to nominate a Supreme Court justice, and it is the Senate's constitutional right to act as a check on the president and withhold its consent."

McConnell was far from the only Republican to speak out in favor of waiting until after the election to consider any Supreme Court nominee.

"It has been 80 years since a Supreme Court vacancy was nominated and confirmed in an election year," Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas said at the time. "There is a long tradition that you don't do this in an election year."

Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who now chairs the Judiciary Committee which would be tasked with holding hearings for the person Trump nominates, was adamant back in 2016 that no vote on Garland should be held so close to an election. "I strongly support giving the American people a voice in choosing the next Supreme Court nominee by electing a new president," he tweeted.

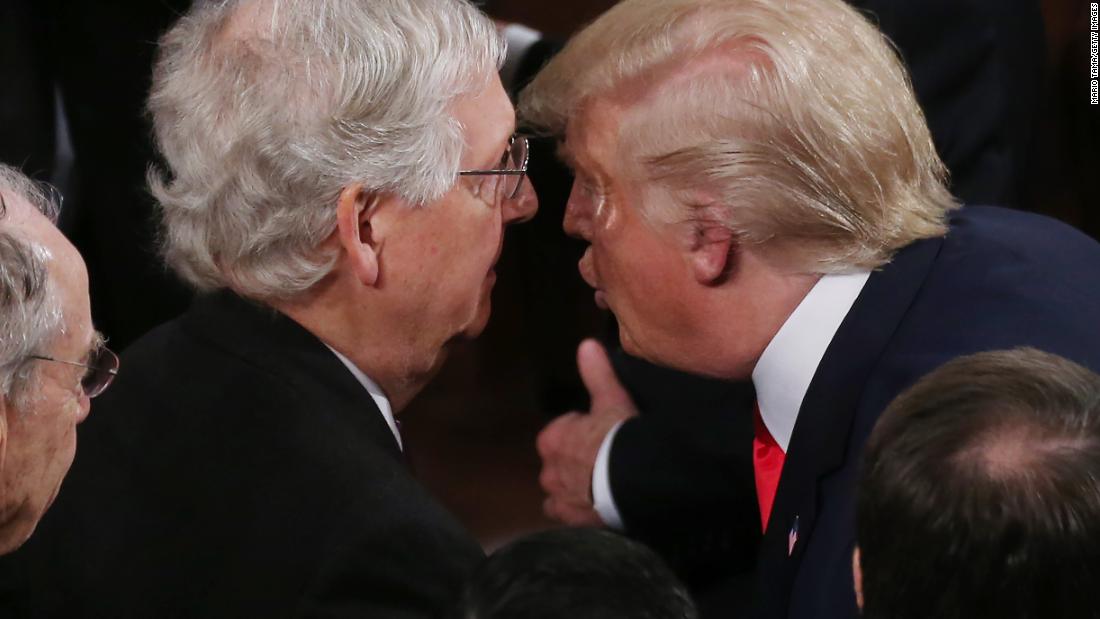

The record then is quite clear. Senate Republicans -- from McConnell on down -- opposed even holding hearings for Garland because the vacancy came in an election year. So now, with just 46 days left before the November election -- and with Trump trailing former Vice President Joe Biden by mid- to upper single digits in most national polling, what's changed, exactly?

The answer, of course, is that Senate Republicans now have one of their own in the White House -- and a political forecast that suggests they may not have another chance anytime soon (like, the next decade or so) to install another conservative on the Supreme Court. And a President, in Trump, who has made absolutely clear not just that he would push to fill a vacancy before the end of his term but who recently released a list of people he might pick.

And so, Senate Republicans are faced with a choice between an unstoppable force (Trump's insistence that he will fill the vacancy and McConnell's promise of a floor vote for whoever he picks) and an immoveable object (their well-documented opposition to just such a scenario back in 2016).

(Yes, I know that some Republicans will try to thread that needle by noting that Obama was term-limited and so there was a certainty that a new president would be elected in 2016, while Trump could still come back to win a second term in November and, therefore, the two situations are not directly comparable. To that I say: Come on, man. We're all adults. Lets just be honest with one another.)

In a way, that Trump's first term ends with the highest of high-profile tests of whether Senate Republicans are loyal to him or to their past stated principles is incredibly fitting. Ever since Trump conducted a hostile takeover of the Republican Party during the 2016 primary campaign, elected GOP officials have been content to go along with his remaking of their party (and of politics more generally) under the belief that as long as they got things they wanted in the deal -- tax cuts, more conservative judges on the federal bench -- it would be worth it.

Time and time again, as Trump has bent -- and broken -- the bounds of normal presidential behavior, Senate Republicans have, largely, stood behind him or remained mum. Sure, there's the occasional tsk-tsking or "Well, that's not the way I would have done it" quote, but, generally speaking, any resistance to Trump within the GOP has been pulverized by the fear of political reprisal from a President who demands total fealty.

So now what? A vote to confirm a Supreme Court justice (or not) is one of the most consequential -- politically and historically -- that any senator can and will make. (The vote by Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine to confirm Kavanaugh may well wind up costing her the seat this fall.) How Republican senators vote on the eventual nominee will, to quote the Violent Femmes, go down on their permanent record.

The work of the next days (and weeks) for McConnell will be to determine if he has 50 Republican votes for Trump's nominee. (It's hard to see how ANY Democrat will vote for Trump's pick given the Garland precedent.) Some of that equation will depend on who Trump picks. The more conservative the choice, the more likely that moderates like Collins and Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska are to vote "no." (Collins and Murkowski, as well as Graham and Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, have said in recent years that they would oppose any attempt to fill a Supreme Court vacancy so close to an election.)

If McConnell cannot muster the votes he needs to confirm Trump's pick prior to the November election, it's possible he would bring the Senate back in a lame-duck session after the election in hopes of gaining a few more votes. The theory of such a move would be that endangered GOP senators who had either won or lost in November would be freer to cast votes without fear of political reprisal. (Note in McConnell's statement that he didn't say the Senate would vote on Trump's pick before the election; he just said the Senate would vote on the pick.)

The move by McConnell in the hours following GInsburg's death sets a very clear choice for the other 52 Republican senators: Either you are with Trump and McConnell or you are against them. If past is prologue, that will be a tough duo for most Senate Republicans to oppose.

"loyalty" - Google News

September 19, 2020 at 09:49AM

https://ift.tt/2FI3Pc3

RBG's death means Republican senators will face the ultimate test of their loyalty to Trump - CNN

"loyalty" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VYbPLn

https://ift.tt/3bZVhYX

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "RBG's death means Republican senators will face the ultimate test of their loyalty to Trump - CNN"

Post a Comment